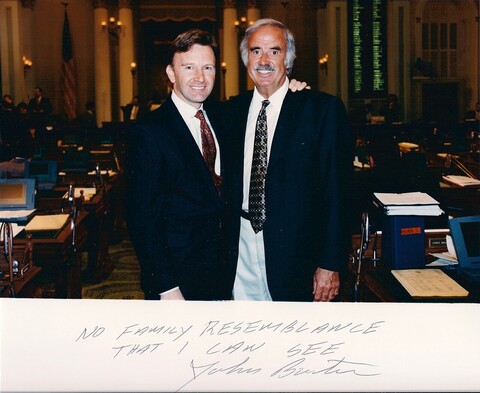

With my political nemesis and friend, John Burton, 1996

If the name John L. Burton doesn't mean anything to you, then you likely slept through the last six decades of California and national politics. A former state legislator, United States Congressman, twice-chairman of the California Democratic Party, and the godfather of all liberal San Francisco politicians for the last half-century, he died today at age 92.

First elected to the California State Assembly in 1964 representing San Francisco (to put down his leftist marker, on his first day in Sacramento he introduced a resolution commending North Vietnam's Communist leader Ho Chi Minh), John went on to win a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1974, where he served alongside his older brother Phillip. John retired from Congress in 1983 to battle a terrible and publicly acknowledged cocaine addiction. Five years later he staged a comeback and won election to his old State Assembly seat; later he served as president pro tempore of the California State Senate, and then he closed out his political career as the chairman of the California Democratic Party (2009-2017). His long-awaited memoir, "I Yell Because I Care," was published just three days ago.

I served with John in the State Assembly during his second career in that chamber, and I don't think I fought longer and harder against any other Democrat. We had absolutely nothing in common and were, by definition, political enemies. And yet….

Before I was born in 1957, my mother Alice was pretty and popular, and with the makings of a professional dancer. She left home after high school graduation and rented a Mission District flat in San Francisco with two girlfriends. Taking a cocktail waitress job at the Cable Car Village, she liked the two bartenders with whom she worked—boyhood pals named Johnny Burton and Jack Barone. Johnny was a quick-witted aspiring law student. Jack was Italian and just as charming, with wavy dark hair, a slender athletic build from his years as a Golden Gloves boxer, a big smile, and an easy-going manner. He worked days as an apprentice carpenter hoping to break into the construction business. Jack and Alice began seeing each other after work, but she kept their dating a secret at his request. The secret ended when she became pregnant; Jack refused to marry her, and so my mother asked my grandparents to raise me when I was born.

Almost forty years later, on the day I became a member of the California State Assembly, the first member of the legislature to welcome my mother and me to the chamber was former United States Congressman and the current chairman of the Assembly Rules Committee, the Honorable John L. Burton of San Francisco. Mom smiled as she greeted her ex-bartender colleague with, "Hello, you old bastard!" As they embraced and kissed, she told him, "Johnny, you look out for Jimmy up here or I'll come back and knock the hell out of you." During my Sacramento tenure, Democrat John Burton fought many legislative battles against Republican James Rogan, but for as long as I was there, "papa John" looked out for me.

Long before I had ever met my biological father (or knew of the Burton-Barone-Rogan connection), as a teenage kid I snuck into a 1972 George McGovern for president fundraising gala at the San Francisco Hilton Hotel, where I was hoping to collect campaign buttons and political autographs for my collection. At the end of the dinner, and as the crowd departed, I saw Assemblyman John Burton standing nearby. He wore on his lapel a type of McGovern campaign button incorporating the American flag and a peace symbol that I had never seen before (or since). After introducing myself, I told him I collected political memorabilia and asked him to give me the badge. John didn't want to part with it, but my zeal wore him down and he relented.

Twenty-four years after he gave me the badge, Johnny and I were serving together in the State Assembly as colleagues. One day I wore his old McGovern button in my lapel and struck up a conversation with him in the chamber while waiting to see if he recognized my vintage treasure. Sure enough, after a few moments he asked about it. I recounted the story for him. "Those were the good old days," he sighed.

I sought to draw him out: "You mean the good old days when liberalism was on the rise? You mean the days when liberals believed they could solve the ills of the world, and when idealistic antiwar activists marched for world peace?"

He looked at me dismissively. "No," he said. "I don't mean any of that shit. I mean the good old days—when we could take money out of the Assembly Rules Committee budget and use it to pay for our fuckin' campaign buttons!"

I won election to Congress in 1996; in 2000, I ran unsuccessfully for a third term following my role in the impeachment of President Clinton. A couple of weeks before my defeat, I ran into Johnny outside the Rayburn House Office Building. After catching up on family, he asked how my campaign was going. I shared the uphill road that I faced that year in what proved the most expensive and hardest fought House race in American history. He asked me a pointed question: "Why the hell do you want a job where you have to kill yourself every day for two years just for the privilege of hanging on to it by your fingernails?"

I had never thought about it in those terms. After pausing to reflect on his question, I replied, "Johnny, I guess it's like the janitor whose job was to shovel shit behind the circus elephants. For twenty years, all he did was shovel and gripe, shovel and gripe, shovel and gripe. Finally, after hearing the janitor complain every day for two decades, the circus manager approached him and asked, 'If you hate your job so much, then why don't you quit?'

"What?" replied the shocked janitor at the radical suggestion. "And give up show business?"

Politics is a business filled with its share of phonies and sharpies, and where insincerity can be far more prevalent and rewarding than honesty and consistency. In all my years in politics, I never met a fiercer opponent—or met a more genuinely old-school liberal warrior—than John Burton. His heart bled for the poor and downtrodden. His politics were knuckles-down and take-no-prisoners, and his word was his bond. He believed in what he advocated, he fought like hell to beat you, but he never took fervent but sincere opposition personally. That is why, along with so many of our conservative Republican former colleagues, I mourn deeply the passing of a politician on the far side of the other aisle.

Rest in peace, Johnny.

* * * * *